We had a lively session on ethics and legal issues at the Jisc Effective Learning Analytics workshop last week, kicking it off by outlining some of the key questions in this area:

- Who should have access to data about students’ online activities?

- Are there any circumstances when collecting data about students is unacceptable/undesirable?

- Should students be allowed to opt out of data collection?

- What should students be told about the data collected on their learning?

- What data should students be able to view about themselves?

- What are the implications of institutions collecting data from non-institutional sources e.g. Twitter?

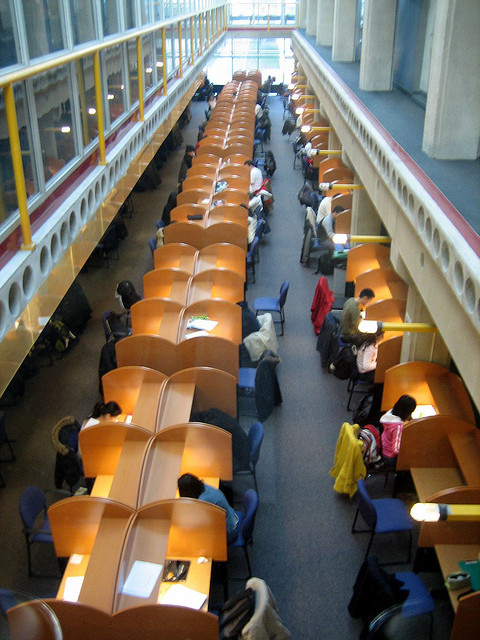

Photo: Students Studying by Christopher Porter CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Concern was also expressed about the metrics being used for analytics – how accurate and appropriate are they and could it be dangerous to base interventions by tutors on metrics which portray an incomplete picture of student activity?

A number of the participants had already been thinking in detail about how to tackle these issues. There was a consensus that learning analytics should be carried out primarily to improve learning outcomes and for the students’ benefit. Analytics should be conducted in a way that would not adversely affect learners based on their past attainment, behaviour or perceived lack of chance for success. The group felt that the sector should not engage with the technical and logistical aspects of learning analytics without first making explicit the legal and ethical issues and understanding our obligations towards students.

Early conversations with students were thought to be vital so that there were no surprises. It was suggested that Informed consent is key – not just expecting students to tick a box saying they’ve read the institution’s computing regulations. Researchers elsewhere have begun to examine many of these areas too – see the paper for example by Sharon Slade and Paul Prinsloo: Learning analytics: ethical issues and dilemmas.

Mike Day at Nottingham Trent University found that students in the era of Google and Facebook already expect data to be being collected about their learning. His institution’s approach has been to make the analytics process a collaboration between the learner and the institution. They have for instance agreed with students that it’s appropriate and helpful for both themselves and their tutors to be able to view all the information held about them.

Another issue discussed at some length was around the ethics of learners’ data travelling with them between institutions. Progress is being made on a unique learner number, and the Higher Education Data and Information Improvement Programme (HEDIIP) is developing more coherent data structures for transferable learner records. It will be possible for data on the learning activities of individuals to be transferred between schools, colleges and universities. But what data is appropriate to transfer? Should you be tainted for the rest of your academic life by what you got up to at school? On the other hand could some of that information prove vital in supporting you as you move between institutions?

Data on disabilities might be one such area where it could be helpful for a future institution to be able to cater for a learner’s special needs. Ethically this may best be under the control of the student who can decide what information to present about their disability. However the technology may be in place to detect certain disabilities automatically such as dyslexia – so the institution might have some of this information whether the student wants them to know it or not.

Who owns the data about a students’ lifelong learning activity is another issue. Institutions may own it for a time, but once that student has left the institution is it appropriate to hold onto it? Perhaps the learner should take ownership of it, even if it is held securely by an institution or an outside agency. There may be a fundamental difference between attainment data and behavioural data, the latter being more transitory and potentially less accurate than assessment results and grades – and therefore it should be disposed of after a certain period.

There are of course different ethical issues involved when data on learning activities is anonymised or aggregated across groups of students. One parallel we discussed was that of medicine. A learner might visit a tutor in the way that a patient visits a GP.

The doctor chats to the patient about their ailment with the patient’s file including their previous medical history in front of them. Combining what the patient says with physical observations and insight from the patient’s records the doctor then makes a diagnosis and prescribes some treatment or suggests a change in lifestyle.

Meanwhile:

A tutor chats to a student about an issue they’re having with their studies and has analytics on their learning to date on a computer in front of them as they talk. The analytics provides additional insight to what the student is saying so the tutor is able to make some helpful suggestions and provide additional reading materials or some additional formative assessment to the student.

In both scenarios the professional takes notes on the interaction which are themselves added to the individual’s records. All the information is held under the strictest confidentiality. However the data in both scenarios can also be anonymised for research purposes, enabling patterns to be discovered and better treatment/advice to be provided to others in the future.

So in order to help institutions navigate their way around the complexities would a code of practice or guidelines be of interest to institutions? The consensus was yes it would and this was borne out in voting by the wider group later in the day. The schools sector has already developed codes of practice and obviously the NHS is well advanced in the ethics of data collection already so there is much to be learned from these professions – and from research ethics committees in many of our own institutions. There would need to be consultation with the various UK funding bodies – and working closely with the National Union of Students was seen as key to ensuring adoption.

A code of practice for learning analytics would have to be clearly scoped, easily understandable and generic enough to have wide applicability across institutions. The primary audiences are likely to be students, tutors and senior management. Mike at Nottingham Trent found the key to success was a four-way partnership between technology providers (who were required to adapt their products to meet ethical concerns), the IT department, students and tutors.

There was a strong consensus in the group that this work would significantly help to allay the fears of students and, often just as vocally, staff in their institutions in order to explore the real possibilities of using learning analytics to aid retention and student success. In fact some stakeholders considered it an essential step at their universities and colleges before they could make progress. Developing a code of practice for learning analytics will therefore be a key area of work for Jisc over the coming months.